A is for API - Introducing Static HTTP Requests

Dillon Kearns

I'm excited to announce a new feature that brings elm-pages solidly into the JAMstack: Static HTTP requests. JAMstack stands for JavaScript, APIs, and Markup. And Static HTTP is all about pulling API data into your elm-pages site.

If you’ve tried elm-pages, you may be thinking, "elm-pages hydrates into a full Elm app... so couldn’t you already make HTTP requests to fetch API data, like you would in any Elm app?" Very astute observation! You absolutely could.

So what's new? It all comes down to these key points:

- Less boilerplate

- Improved reliability

- Better performance

Let's dive into these points in more detail.

Less boilerplate

Let's break down how you perform HTTP requests in vanilla Elm, and compare that to how you perform a Static HTTP request with elm-pages.

Anatomy of HTTP Requests in Vanilla Elm

- Cmd for an HTTP request on init (or update)

- You receive a

Msginupdatewith the payload - Store the data in

Model - Tell Elm how to handle

Http.Errors (including JSON decoding failures)

Anatomy of Static HTTP Requests in elm-pages

viewfunction specifies someStaticHttpdata, and a function to turn that data into yourviewandheadtags for that page

That's actually all of the boilerplate for StaticHttp requests!

There is a lifecycle, because things can still fail. But the entire Static HTTP lifecycle happens before your users have even requested a page. The requests are performed at build-time, and that means less boilerplate for you to maintain in your Elm code!

Let's see some code!

Here's a code snippet for making a StaticHttp request. This code makes an HTTP request to the Github API to grab the current number of stars for the elm-pages repo.

import Pages.StaticHttp as StaticHttp

import Pages

import Head

import Secrets

import Json.Decode.Exploration as Decode

view :

{ path : PagePath Pages.PathKey

, frontmatter : Metadata

}

->

StaticHttp.Request

{ view : Model ->

View -> { title : String, body : Html Msg }

, head : List (Head.Tag Pages.PathKey)

}

view page =

(StaticHttp.get

(Secrets.succeed

"https://api.github.com/repos/dillonkearns/elm-pages")

(Decode.field "stargazers_count" Decode.int)

)

|> StaticHttp.map

(\starCount ->

{ view =

\model renderedMarkdown ->

{ title = "Landing Page"

, body =

[ header starCount

, pageView model renderedMarkdown

]

}

, head = head starCount

}

)

head : Int -> List (Head.Tag Pages.PathKey)

head starCount =

Seo.summaryLarge

{ canonicalUrlOverride = Nothing

, siteName = "elm-pages - "

++ String.fromInt starCount

++ " GitHub Stars"

, image =

{ url = images.iconPng

, alt = "elm-pages logo"

, dimensions = Nothing

, mimeType = Nothing

}

, description = siteTagline

, locale = Nothing

, title = "External Data Example"

}

|> Seo.website

The data is baked into our built code, which means that the star count will only update when we trigger a new build. This is a common JAMstack technique. Many sites will trigger builds periodically to refresh data. Or better yet, use a webhook to trigger new builds whenever new data is available (for example, if you add a new blog post or a new page using a service like Contentful).

Notice that this app's Msg, Model, and update function are not involved in the process at all! It's also worth noting that we are passing that data into our head function, which allows us to use it in our <meta> tags for the page.

The StaticHttp functions are very similar to Elm libraries

you've likely used already, such as elm/json or elm/random.

If you don't depend on any StaticHttp data, you use StaticHttp.succeed,

similar to how you might use Json.Decode.succeed, Random.constant,

etc.

import Pages.StaticHttp as StaticHttp

StaticHttp.succeed

{ view =

\model renderedMarkdown ->

{ title = "Landing Page"

, body =

[ header

, pageView model renderedMarkdown

]

}

, head = head

}

This is actually the same as our previous example that had a StaticHttp.request, except that it doesn't make a request or have the

stargazer count data.

Secure Secrets

A common pattern is to use environment variables in your local environment or your CI environment in order to securely manage

auth tokens and other secure data. elm-pages provides an API for accessing this data directly from your environment variables.

You don't need to wire through any flags or ports, simply use the Pages.Secrets module (see the docs for more info). It will take care of masking the secret data for you

so that it won't be accessible in the bundled assets (it's just used to perform the requests during the build step, and then

it's masked in the production assets).

The Static HTTP Lifecycle

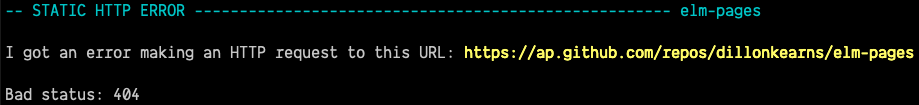

If you have a bad auth token in your URL, or your JSON decoder fails, then that code will never run for your elm-pages site. Instead, you'll get a friendly elm-pages build-time error telling you exactly what the problem was and where it occurred (as you're familiar with in Elm).

These error messages are inspired by Elm's famously helpful errors. They're designed to point you in the right direction, and provide as much context as possible.

Which brings us to our next key point...

Improved reliability

Static HTTP requests are performed at build-time. Which means that if you have a problem with one of your Static HTTP requests, your users will never see it. Even if a JSON decoder fails, elm-pages will report back the decode failure and wait until its fixed before it allows you to create your production build.

Your API might go down, but your Static HTTP requests will always be up (assuming your site is up). The responses from your Static requests are baked into the static files for your elm-pages build. If there is an API outage, you of course won't be able to rebuild your site with fresh data from that API. But you can be confident that, though your build may break, your site will always have a working set of Static HTTP data.

Compare this to an HTTP request in a vanilla Elm app. Elm can guarantee that you've handled all error cases. But you still need to handle the case where you have a bad HTTP response, or a JSON decoder fails. That's the best that Elm can do because it can't guarantee anything about the data you'll receive at runtime. But elm-pages can make guarantees about the data you'll receive! Because it introduces a new concept of data that you get a snapshot of during your build step. elm-pages guarantees that this frozen moment of time has no problems before the build succeeds, so we can make even stronger guarantees than we can with plain Elm.

Better performance

The StaticHttp API also comes with some significant performance boosts. StaticHttp data is just a static JSON file for each page in your elm-pages site. That means that:

- No waiting on database queries to fetch API data

- Your site, including API responses, is just static files so it can be served through a blazing-fast CDN (which serves files from the nearest server in the user's region)

- Scaling is cheap and doesn't require an Ops team

elm-pagesintelligently prefetches the Static HTTP data for a page when you're likely to navigate to that page, so page loads are instant and there's no spinner waiting to load that initial dataelm-pagesoptimizes yourStaticHttpJSON data, stripping out everything but what you use in your JSON decoder

JSON Optimization

The JSON optimization is made possible by a JSON parsing library created by Ilias Van Peer. Here's the pull request where he introduced the JSON optimization functionality: github.com/zwilias/json-decode-exploration/pull/9.

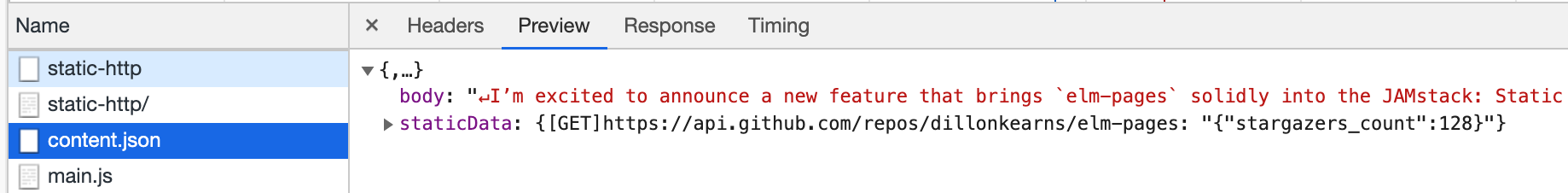

Let's take our Github API request as an example. Our Github API request from our previous code snippet (https://api.github.com/repos/dillonkearns/elm-pages) has a payload of 5.6KB (2.4KB gzipped). That size of the optimized JSON drops down to about 3% of that.

You can inspect the network tab on this page and you'll see something like this:

If you click on Github API link above and compare it, you'll see that it's quite a bit smaller! It just has the one field that we grabbed in our JSON decoder.

This is quite nice for privacy and security purposes as well because any personally identifying information that might be included in an API response you consume won't show up in your production bundle (unless you were to explicitly include it in a JSON decoder).

Comparing StaticHttp to other JAMstack data source strategies

You may be familiar with frameworks like Gatsby or Gridsome which also allow you to build data from external sources into your static site. Those frameworks, however, use a completely different approach, using a GraphQL layer to store data from those data sources, and then looking that data up in GraphQL queries from within your static pages.

This approach makes sense for those frameworks. But since elm-pages is built on top of a language that already has an excellent type system, I wanted to remove that additional layer of abstraction and provide a simpler way to consume static data. The fact that Elm functions are all deterministic (i.e. given the same inputs they will always have the same outputs) opens up exciting new approaches to these problems as well. One of Gatsby's stated reasons for encouraging the use of their GraphQL layer is that it allows you to have your data all in one place. But the elm-pages StaticHttp API gives you similar benefits, using familiar Elm techniques like map, andThen, etc to massage your data into the desired format.

Future plans

I'm looking forward to exploring more possibilities for using static data in elm-pages. Some things I plan to explore are:

- Programatically creating pages using the Static HTTP API

- Configurable image optimization (including producing multiple dimensions for

srcsets) using a similar API - Optimizing the page metadata that is included for each page (i.e. code splitting) by explicitly specifying what metadata the page depends on using an API similar to StaticHttp

Getting started with StaticHttp

You can take a look at this an end-to-end example app that uses the new StaticHttp library to get started.

Or just use the elm-pages-starter repo and start building something cool! Let me know your thoughts on Slack, I'd love to hear from you! Or continue the conversation on Twitter!